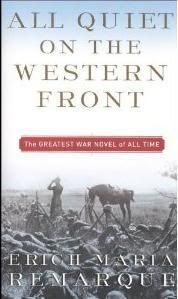

Since the passing of Frank Buckles, the last surviving American veteran of World War I, I’ve been interesting in reading some books from that period. So company XO lent me his copy of All Quiet on the Western Front, a book most people – if ever – read in high school.

Since the passing of Frank Buckles, the last surviving American veteran of World War I, I’ve been interesting in reading some books from that period. So company XO lent me his copy of All Quiet on the Western Front, a book most people – if ever – read in high school.This post isn’t so much a review of the book as it is a selection of the parts I identified the most with. Our present conflict is a far cry from high casualty, static battle lines that generation fought, but there are certain things about the effects of war that I’ve come to understand better through this book.

Early in the book, the author talks about how war impacts younger soldiers more than older ones. Having joined the Army as a an older guy (33) with a family, I have a better frame of reference with which to deal with stuff.

For the younger guys who join right after high school, this is often all they’ve ever known. To a certain degree, life in the Army limits one’s experience, and if your formative adult years are spent in combat, it affects your perspectives for the rest of your life. It’s hard for the younger guys to keep perspective on that.

Second, I identified with the disconnect the author felt when he was on leave. His father wants to hear about war stories and takes him around town, but all the author wants is to just rest. Things that were important to him before pale in comparison to his front-line struggle for survival, leaving him feel empty.

I sometimes feel that way when I go on Facebook and see the ways people keep themselves busy. While I don’t consider myself “scarred,” by my experience in Afghanistan, I do look at things differently now. Many things just seem … I don’t know … less important.

Lastly, I understand what the author says about the inexplicable randomness of war. In WWI, an artillery shell could demolish a concrete bunker designed to protect people from such attacks, while a person could survive a ten-hour bombardment in the open without a scratch. There’s simply no explaining such things.

The same is true of the rocket attacks we experience here. One learns to develop a sense of nihilism about it all – if it’s your time, there’s simply nothing you can do about it, so there’s no use worrying. The fate of our lives can be determined by a matter of inches and minutes.

It’s not a happy book – it wasn’t meant to be. It was supposed to illustrate the price young men pay in war, and convey the sadness of a generation of men destroyed by the experience.

To this point I haven’t seen death in war, but I have seen its wreckage.

No comments:

Post a Comment