The cover for Edward Lendel's book about the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne describes it as "the epic battle that ended the First World War." This is a bit of an exaggeration. True, it lasted until the end of the war, but it was one of several -- "a" battle, but not "the."

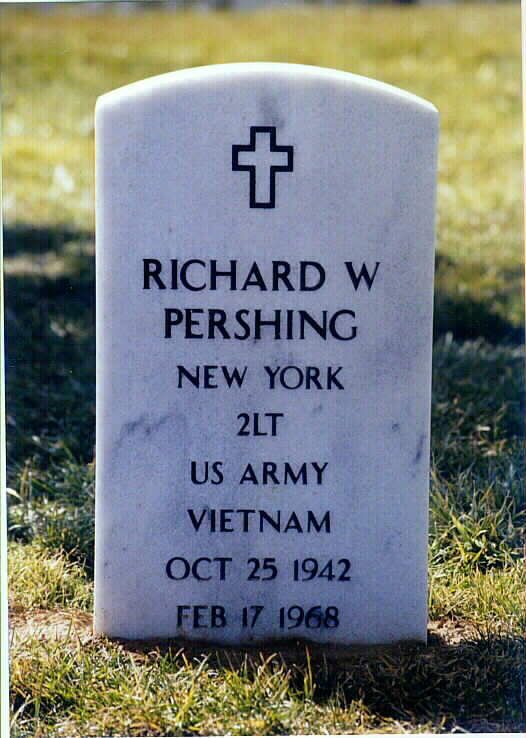

The author starts with the 1915 tragedy that claimed the lives of General John Pershing's wife and three daughters -- a loss from which Pershing never fully recovered. Only his young son Warren was spared. [His son Richard, a Yale classmate of John Kerry, died in Vietnam in 1968.]

In the second part, he briefly covers the U.S. entry into the war, the challenges of creating a two million-man army from scratch, and the successes of summer 1918. On September 26, 1918, the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne began, and a day-by-day record until the Armistice takes up the rest of the book.

This is a good book to understand the Doughboy experience, but a poor one if you're trying to understand the tactical movements -- the maps only give the broadest views of the conflict, and mark very few of the points listed in the book.

Compared to the current Afghan counterinsurgency, I can't imagine a more different war -- draft army, little or no real training, little civilian interaction, miserable living conditions, short duration, accurate enemy counterfire, trenches, infantry charges, and unimaginative leadership. In all instances, our current conflict is significantly different.

The scale and intensity of the horrors, too, overwhelm the imagination. Our involvements in Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted in between 4500 and 6000 military personnel killed in the past ten years. The Meuse-Argonne killed over 26,000 in six weeks.

There's a good discussion at the end about how good a general Pershing was. The critic would say the draftees' training program stunk, he was too arrogant to learn from the European experience, he was a mediocre general, he should have reinforced the Allies rather than insisting on a separate U.S. force, or a number of other things. The book certainly pulls no punches about the Americans' early failures in applying combined-arms tactics, and savages the generals for insisting on murderous frontal assaults.

Those point are all valid, but I look at the fact it took a mere six weeks in the Meuse-Argonne to finish the war. How long would it have taken to "get it right," rather than "get it done"? Yes, the human cost is incalculable, but Pershing read the reports and saw the numbers. He may not have been brilliant, but neither was he blind. I have to respect him for that.

At the end of the war, Warren joined his father in France, and they were feted everywhere they went. I'm sure it was little comfort compared to what they, as a family, had lost during the war years, but in a sense, their experience mirrored that of countless families, and epitomizes what that war truly took from the world.

What haunts me the most, though, is something not stated in the book. After growing up with the tragic loss of his mother and all his sisters, Warren had two sons of his own, one of which would graduate from Yale and befriend another young man named John Kerry before going to Vietnam.

2LT Richard Pershing was killed there in 1968.

The cover for Edward Lendel's book about the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne describes it as "the epic battle that ended the First World War." This is a bit of an exaggeration. True, it lasted until the end of the war, but it was one of several -- "a" battle, but not "the."

The author starts with the 1915 tragedy that claimed the lives of General John Pershing's wife and three daughters -- a loss from which Pershing never fully recovered. Only his young son Warren was spared. [His son Richard, a Yale classmate of John Kerry, died in Vietnam in 1968.]

In the second part, he briefly covers the U.S. entry into the war, the challenges of creating a two million-man army from scratch, and the successes of summer 1918. On September 26, 1918, the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne began, and a day-by-day record until the Armistice takes up the rest of the book.

This is a good book to understand the Doughboy experience, but a poor one if you're trying to understand the tactical movements -- the maps only give the broadest views of the conflict, and mark very few of the points listed in the book.

Compared to the current Afghan counterinsurgency, I can't imagine a more different war -- draft army, little or no real training, little civilian interaction, miserable living conditions, short duration, accurate enemy counterfire, trenches, infantry charges, and unimaginative leadership. In all instances, our current conflict is significantly different.

The scale and intensity of the horrors, too, overwhelm the imagination. Our involvements in Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted in between 4500 and 6000 military personnel killed in the past ten years. The Meuse-Argonne killed over 26,000 in six weeks.

There's a good discussion at the end about how good a general Pershing was. The critic would say the draftees' training program stunk, he was too arrogant to learn from the European experience, he was a mediocre general, he should have reinforced the Allies rather than insisting on a separate U.S. force, or a number of other things. The book certainly pulls no punches about the Americans' early failures in applying combined-arms tactics, and savages the generals for insisting on murderous frontal assaults.

Those point are all valid, but I look at the fact it took a mere six weeks in the Meuse-Argonne to finish the war. How long would it have taken to "get it right," rather than "get it done"? Yes, the human cost is incalculable, but Pershing read the reports and saw the numbers. He may not have been brilliant, but neither was he blind. I have to respect him for that.

At the end of the war, Warren joined his father in France, and they were feted everywhere they went. I'm sure it was little comfort compared to what they, as a family, had lost during the war years, but in a sense, their experience mirrored that of countless families, and epitomizes what that war truly took from the world.

The cover for Edward Lendel's book about the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne describes it as "the epic battle that ended the First World War." This is a bit of an exaggeration. True, it lasted until the end of the war, but it was one of several -- "a" battle, but not "the."

The author starts with the 1915 tragedy that claimed the lives of General John Pershing's wife and three daughters -- a loss from which Pershing never fully recovered. Only his young son Warren was spared. [His son Richard, a Yale classmate of John Kerry, died in Vietnam in 1968.]

In the second part, he briefly covers the U.S. entry into the war, the challenges of creating a two million-man army from scratch, and the successes of summer 1918. On September 26, 1918, the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne began, and a day-by-day record until the Armistice takes up the rest of the book.

This is a good book to understand the Doughboy experience, but a poor one if you're trying to understand the tactical movements -- the maps only give the broadest views of the conflict, and mark very few of the points listed in the book.

Compared to the current Afghan counterinsurgency, I can't imagine a more different war -- draft army, little or no real training, little civilian interaction, miserable living conditions, short duration, accurate enemy counterfire, trenches, infantry charges, and unimaginative leadership. In all instances, our current conflict is significantly different.

The scale and intensity of the horrors, too, overwhelm the imagination. Our involvements in Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted in between 4500 and 6000 military personnel killed in the past ten years. The Meuse-Argonne killed over 26,000 in six weeks.

There's a good discussion at the end about how good a general Pershing was. The critic would say the draftees' training program stunk, he was too arrogant to learn from the European experience, he was a mediocre general, he should have reinforced the Allies rather than insisting on a separate U.S. force, or a number of other things. The book certainly pulls no punches about the Americans' early failures in applying combined-arms tactics, and savages the generals for insisting on murderous frontal assaults.

Those point are all valid, but I look at the fact it took a mere six weeks in the Meuse-Argonne to finish the war. How long would it have taken to "get it right," rather than "get it done"? Yes, the human cost is incalculable, but Pershing read the reports and saw the numbers. He may not have been brilliant, but neither was he blind. I have to respect him for that.

At the end of the war, Warren joined his father in France, and they were feted everywhere they went. I'm sure it was little comfort compared to what they, as a family, had lost during the war years, but in a sense, their experience mirrored that of countless families, and epitomizes what that war truly took from the world.

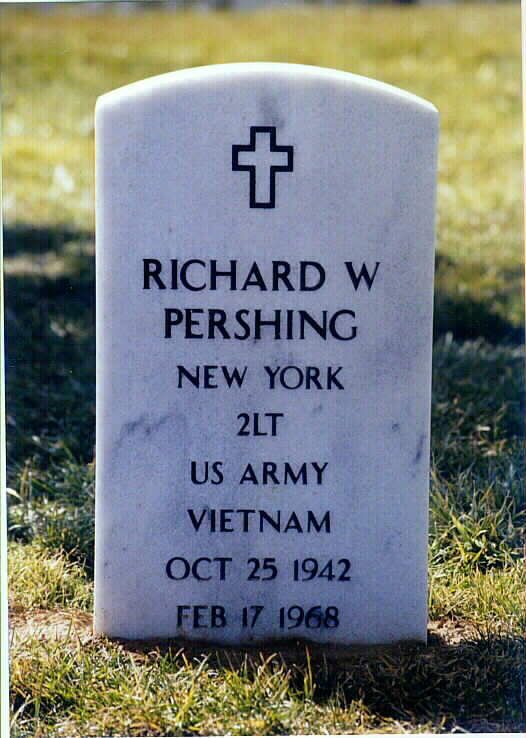

What haunts me the most, though, is something not stated in the book. After growing up with the tragic loss of his mother and all his sisters, Warren had two sons of his own, one of which would graduate from Yale and befriend another young man named John Kerry before going to Vietnam.

2LT Richard Pershing was killed there in 1968.

What haunts me the most, though, is something not stated in the book. After growing up with the tragic loss of his mother and all his sisters, Warren had two sons of his own, one of which would graduate from Yale and befriend another young man named John Kerry before going to Vietnam.

2LT Richard Pershing was killed there in 1968.

No comments:

Post a Comment