At least, not in a security clearance interview....

At least, not in a security clearance interview....

Thursday, September 30, 2021

Tuesday, September 28, 2021

Sunday, September 26, 2021

Anna Maria Boyer

The Battle of Long Island in August 1776 wasn't particularly costly to George Washington's Continental Army in terms of deaths, but it cost the life of German immigrant Anna Maria Boyer's brother, Peter.

And the campaign for New York City was far from over.

Following the evacuation of his army from Brooklyn Heights, Washington maintained control of Manhattan, but his position was still vulnerable. He feared the British would land on New York's mainland and gradually encircle him. Instead, the British landed on Manhattan's eastern shore, at Kipp's Bay, on September 15th. The result was an embarrassing failure to contest the landing.

Following the evacuation of his army from Brooklyn Heights, Washington maintained control of Manhattan, but his position was still vulnerable. He feared the British would land on New York's mainland and gradually encircle him. Instead, the British landed on Manhattan's eastern shore, at Kipp's Bay, on September 15th. The result was an embarrassing failure to contest the landing.

This failure forced Washinton to make a choice:

To prevent the British from taking control of the Hudson River and driving a wedge between New York and New England, Washington put his trust in the twin defense works of Fort Lee and Fort Washington. These two forts overlooked the Hudson River from both the east and west banks.

And to keep the Royal Navy from trapping the entire Continental Army on Manhattan, Washington moved everyone not involved in the defense of Fort Washington over King's Bridge to Yonkers. British general Williame Howe pursued, and fought the Battle of White Plains on October 28th. It was a British victory, but it was far from decisive.

What frustrated Howe was now that Washington was on the mainland, he could retreat in any direction. Instead of chasing Washington through unfamiliar territory, Howe decided to return to Manhattan to lay seige the fortifications guarding the Hudson River.

Aided by insider information provided by a turncoat, Howe attacked Fort Washington on November 16th, 1776, with 8,000 troops advancing from three directions.

As the outer defenses fell, retreating Patriots flooded the fort, until it became so overcrowded that the location could not be defended without great loss of life. Instead holding out until December (as its commander had hoped), the Continental forces surrendered that afternoon.

The Battle of Fort Washington was in equal measures a tactical masterpiece for Howe and a disaster for the Colonial Army. Although it suffered only 59 soldiers were killed and 96 were wounded, fully 2837 Patriots were taken prisoner.

It was also a tragedy for Anna Maria Boyer. One of those 59 was her husband.

Less than three months after losing her brother Peter in the Battle of Long Island, she lost her husband Johann Jacob Engler at Fort Washington. This left her a 40 year-old widow with eight children to care for, including twins that were still less than two years old.

Forever in history, Peter Boyer and his brother-in-law Johann Jacob Engler will face each other in the rolls of those lost in Captain John Arndt's company during the Revolutionary War. Yet life has a funny way of working out sometimes.

Yet life has a funny way of working out sometimes.

Within two years, Anna Maria Boyer would marry another German immigrant named Johann Philip Achenbach, and they would have three more children by the time she turned 47.

The oldest of the three was named John Philip Achenbach -- Harold Achenbach's great-grandfather.

And the campaign for New York City was far from over.

Following the evacuation of his army from Brooklyn Heights, Washington maintained control of Manhattan, but his position was still vulnerable. He feared the British would land on New York's mainland and gradually encircle him. Instead, the British landed on Manhattan's eastern shore, at Kipp's Bay, on September 15th. The result was an embarrassing failure to contest the landing.

Following the evacuation of his army from Brooklyn Heights, Washington maintained control of Manhattan, but his position was still vulnerable. He feared the British would land on New York's mainland and gradually encircle him. Instead, the British landed on Manhattan's eastern shore, at Kipp's Bay, on September 15th. The result was an embarrassing failure to contest the landing.This failure forced Washinton to make a choice:

- Move his forces north, and abandon New York City,

- Move his forces south to defend the city, and risk losing any chance of retreat, or

- Try to do both, and risk his forces being split in two.

To prevent the British from taking control of the Hudson River and driving a wedge between New York and New England, Washington put his trust in the twin defense works of Fort Lee and Fort Washington. These two forts overlooked the Hudson River from both the east and west banks.

And to keep the Royal Navy from trapping the entire Continental Army on Manhattan, Washington moved everyone not involved in the defense of Fort Washington over King's Bridge to Yonkers. British general Williame Howe pursued, and fought the Battle of White Plains on October 28th. It was a British victory, but it was far from decisive.

What frustrated Howe was now that Washington was on the mainland, he could retreat in any direction. Instead of chasing Washington through unfamiliar territory, Howe decided to return to Manhattan to lay seige the fortifications guarding the Hudson River.

Aided by insider information provided by a turncoat, Howe attacked Fort Washington on November 16th, 1776, with 8,000 troops advancing from three directions.

As the outer defenses fell, retreating Patriots flooded the fort, until it became so overcrowded that the location could not be defended without great loss of life. Instead holding out until December (as its commander had hoped), the Continental forces surrendered that afternoon.

The Battle of Fort Washington was in equal measures a tactical masterpiece for Howe and a disaster for the Colonial Army. Although it suffered only 59 soldiers were killed and 96 were wounded, fully 2837 Patriots were taken prisoner.

It was also a tragedy for Anna Maria Boyer. One of those 59 was her husband.

Less than three months after losing her brother Peter in the Battle of Long Island, she lost her husband Johann Jacob Engler at Fort Washington. This left her a 40 year-old widow with eight children to care for, including twins that were still less than two years old.

Forever in history, Peter Boyer and his brother-in-law Johann Jacob Engler will face each other in the rolls of those lost in Captain John Arndt's company during the Revolutionary War.

Yet life has a funny way of working out sometimes.

Yet life has a funny way of working out sometimes. Within two years, Anna Maria Boyer would marry another German immigrant named Johann Philip Achenbach, and they would have three more children by the time she turned 47.

The oldest of the three was named John Philip Achenbach -- Harold Achenbach's great-grandfather.

Saturday, September 25, 2021

Twins

My grandmother was a twin (fraternal). I have two aunts who are identical twins, and one of those aunts had identical twin daughters.

Yet apart from that, isn't really any pattern of twins in my family history. There is, however, one story that's kind of interesting. You may want to draw this out to keep track of the names.

Mildred and Mabel Shellito were twins, born on August 10th, 1880. Mildred married Harold Achenbach in 1901 and had three children -- two boys and a girl. Mabel married William Parker in 1906 and had only one daughter (b1909).

In choosing a name for her daughter, Mabel picked something that was dear to her -- Mildred. Two years later, Mildred followed suit and named her daughter Mabel.

So here we have two twin sisters with one daughter each -- both of whom are named after their aunts.

Unfortunately, the Spanish influenza struck in 1918, and Mildred (the older one) died from pneumonia in November. (As Dr. Anthony Fauci explained in 2008, "...bacterial pneumonia played a major role in the mortality of the 1918 pandemic.") [Source

Harold did not remarry, and -- realizing that as a "general farmer" near Bay City, MI, he was ill-suited to raise a daughter on his own -- sent Mabel to live with her aunt Mabel and cousin Mildred in Detroit.

At this point, Mabel (the younger one) started going by her middle name, Lucille.

Lucille moved back home as she got older. When she married in 1932, her husband moved in with her and her widower father Harold. The couple had two daughters of her own in the 1930s. The named the first Janice Lee; the second, Mildred Joyce, after her mother and cousin.

Lucille moved back home as she got older. When she married in 1932, her husband moved in with her and her widower father Harold. The couple had two daughters of her own in the 1930s. The named the first Janice Lee; the second, Mildred Joyce, after her mother and cousin.

(Aunt Mabel's daughter Mildred also had a daughter. Just to make things complicated, it turns out her name is Janice, too.)

It turns out Janice Lee passed away recently -- March 30, 2020...

...at the beginning of a similar pandemic to the one that killed her grandmother. She was my sixth cousin, twice removed.

Yet apart from that, isn't really any pattern of twins in my family history. There is, however, one story that's kind of interesting. You may want to draw this out to keep track of the names.

Mildred and Mabel Shellito were twins, born on August 10th, 1880. Mildred married Harold Achenbach in 1901 and had three children -- two boys and a girl. Mabel married William Parker in 1906 and had only one daughter (b1909).

In choosing a name for her daughter, Mabel picked something that was dear to her -- Mildred. Two years later, Mildred followed suit and named her daughter Mabel.

So here we have two twin sisters with one daughter each -- both of whom are named after their aunts.

Unfortunately, the Spanish influenza struck in 1918, and Mildred (the older one) died from pneumonia in November. (As Dr. Anthony Fauci explained in 2008, "...bacterial pneumonia played a major role in the mortality of the 1918 pandemic.") [Source

Harold did not remarry, and -- realizing that as a "general farmer" near Bay City, MI, he was ill-suited to raise a daughter on his own -- sent Mabel to live with her aunt Mabel and cousin Mildred in Detroit.

At this point, Mabel (the younger one) started going by her middle name, Lucille.

Lucille moved back home as she got older. When she married in 1932, her husband moved in with her and her widower father Harold. The couple had two daughters of her own in the 1930s. The named the first Janice Lee; the second, Mildred Joyce, after her mother and cousin.

Lucille moved back home as she got older. When she married in 1932, her husband moved in with her and her widower father Harold. The couple had two daughters of her own in the 1930s. The named the first Janice Lee; the second, Mildred Joyce, after her mother and cousin. (Aunt Mabel's daughter Mildred also had a daughter. Just to make things complicated, it turns out her name is Janice, too.)

It turns out Janice Lee passed away recently -- March 30, 2020...

...at the beginning of a similar pandemic to the one that killed her grandmother. She was my sixth cousin, twice removed.

Friday, September 24, 2021

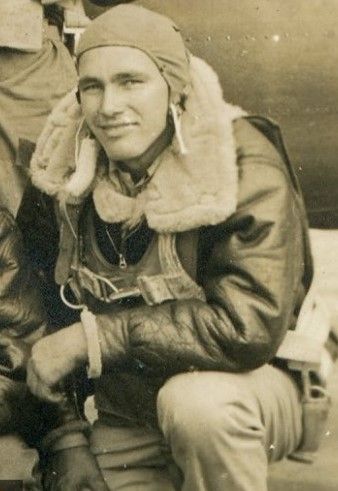

Dean Charles Trippler

It seems Dean Trippler didn’t get along with his father, but I can understand why.

It seems Dean Trippler didn’t get along with his father, but I can understand why.Dean’s mother died when he was 6 years-old, having outlived her newborn eighth child by a mere three days.

That left Charles Trippler with seven children to take care of, ranging from 11 to 2. He did not remarry, and as a farmer, he would have been too busy keeping the roof over their heads to worry about nurturing his third son.

By the time Dean turned 16, he was living with his uncle Victor Pogue – his mother’s brother – who was only 14 years older. As Dean’s uncle, Victor filled a role in his life as a both mentor and surrogate father figure.

So when the U.S. entered World War II and Dean went in to fill out his draft card two weeks after his 18th birthday (on the last day of the Fifth Registration), he listed Uncle Victor -- not his father -- as his “person who will always know your address.”

Dean would go into the Air Force, where he served with the 763rd Bombardment Squadron in the 460th Bombardment Group. The unit was equipped with B-24 Liberators and trained in Georgia in 1943, then assigned to the Mediterranean Theater in January 1944.

Dean rose to the rank of Sergeant, and probably participated in some of the interdiction and close air support missions related to the Allied invasion of southern France (Operation Dragoon).

However, most of the squadron’s missions were strategic bombing, such as the one they began on November 11th, 1944.

That day, the 763rd took off from Spinozzola Air Field in southern Italy on a combat mission to bomb German war installations in Linz, Austria. Dean’s B-24J Liberator flew “in the #3 position in the lead box on the second attack unit.” However, the mission was “called back due to bad weather conditions,” and the planes returned to base.

On arrival back at Spinozzola, however, both Dean’s plane (serial number 42-51737) and another (#42-51845) were missing. The squadron’s operations officer took statements from the other crews in the squadron and filed two Missing Air Crew Reports (#9747 and #9749).

On arrival back at Spinozzola, however, both Dean’s plane (serial number 42-51737) and another (#42-51845) were missing. The squadron’s operations officer took statements from the other crews in the squadron and filed two Missing Air Crew Reports (#9747 and #9749).Dean’s plane was last sighted on a course of 330 degrees at 9:10 a.m. at 23,000 feet. Missing Air Crew Report number 9749 notes that “Disappearance not known until after completion of mission,” and attributed the loss of the two aircraft to "Other: Weather Hazards."

“Due to solid overcast conditions over the Adriatic Sea, there were no witnesses to the disappearance of the crew and aircraft.” That led the operations officer to conclude that the two planes experienced a mid-air collision approximately 24 miles southwest of the (now) Croatian island of Vis, with all crewmen lost.

“Due to solid overcast conditions over the Adriatic Sea, there were no witnesses to the disappearance of the crew and aircraft.” That led the operations officer to conclude that the two planes experienced a mid-air collision approximately 24 miles southwest of the (now) Croatian island of Vis, with all crewmen lost.For his actions in the war, Dean Tripler was awarded the Air Medal with one Oak Leaf Cluster and the Purple Heart.

Today, Dean Charles Trippler is memorialized as “Missing in Action” at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, along with his nine other crewmates.

To my Grandpa Bob, he was a second cousin.

To my Grandpa Bob, he was a second cousin.To Charles Trippler, he was the only one of five sons in the military who never came home.

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

I had a conversation with my sister today, and she asked me what I thought about the whole "vaccinations or regular COVID testing for companies with 100+ people."

I told her I like the way Japan has been doing it, which is no mandatory anything, but if you don't wear a mask you're looked at like something's wrong with you.

So while the U.S. leads Japan in its vaccination rate (Japan only recently crossed the 50% threshold), COVID cases here are still just a fraction of those in the U.S. (The Olympics "spike" in cases here would have been no more than a bump in the U.S.)

I see the U.S. as being so focused on individual rights that we miss the bigger picture, and I think that's too bad. I dislike strong-arm tactics, but I also dislike the amount of misinformation that's negatively influencing people.

She liked the way I phrased the following, and wanted me to write this down, so I'll put it here:

"I would like to see people make decisions based on what's best for society, but what I see is that people tend to make decisions based on what they perceive is best for themselves."

Japan suffers from a higher suicide rate than the U.S. because of its emphasis on social obligations, but I still think there's value in placing others before ourselves.

I told her I like the way Japan has been doing it, which is no mandatory anything, but if you don't wear a mask you're looked at like something's wrong with you.

So while the U.S. leads Japan in its vaccination rate (Japan only recently crossed the 50% threshold), COVID cases here are still just a fraction of those in the U.S. (The Olympics "spike" in cases here would have been no more than a bump in the U.S.)

I see the U.S. as being so focused on individual rights that we miss the bigger picture, and I think that's too bad. I dislike strong-arm tactics, but I also dislike the amount of misinformation that's negatively influencing people.

She liked the way I phrased the following, and wanted me to write this down, so I'll put it here:

"I would like to see people make decisions based on what's best for society, but what I see is that people tend to make decisions based on what they perceive is best for themselves."

Japan suffers from a higher suicide rate than the U.S. because of its emphasis on social obligations, but I still think there's value in placing others before ourselves.

Tuesday, September 21, 2021

Lambros James Matthews

"Lambros" (Λάμπρος) isn't the kind of name you typically see before a family name like "Matthews." Lambros is a Greek name meaning "radiant," and is associated with the word for Easter (Lambri, Λαμπρή).

Nevertheless, Lambros was James Matthews' first name, just as it was his grandfather's. Yet "Matthews" wasn't his grandfather's last name. It was Hatjimathios.

And contrary to what James' father put on the 1930 census, the Hatjimathios family wasn't from Greece. They actually came from Cesme, a town on the Aegean coast of Turkey.

Which explains why he came over in 1921.

Between 1914 and 1922, a large part of the Greek population in Turkey was forced to leave their ancestral homelands of Ionia, Pontus and Eastern Thrace. Those families didn't see themselves as Turkish -- they were Greek, even if they weren't from Greece per se.

That was part of the problem. The new Turkish state saw them as a threat -- much like the Armenians -- and during the 1919-1922 Greco-Turkish War, the Greeks in Turkey suffered numerous atrocities.

I don't know what James' father saw, but he escaped a country at war only a few years ahead of a massive population exchange involving 1.5 million people.

The desire to fit in to his new country -- to not have a target on his back because of his identity -- must have appealed to him greatly. He changed Hatjimathios to Matthews, settled in New Jersey, married an American woman from North Carolina named Inez Juanita Langley, and began a new life.

Lambros James Matthews was my grandfather's cousin. And it was 100 years ago that *his* father, Mathios Hatjimathios, came to America.

Nevertheless, Lambros was James Matthews' first name, just as it was his grandfather's. Yet "Matthews" wasn't his grandfather's last name. It was Hatjimathios.

And contrary to what James' father put on the 1930 census, the Hatjimathios family wasn't from Greece. They actually came from Cesme, a town on the Aegean coast of Turkey.

Which explains why he came over in 1921.

Between 1914 and 1922, a large part of the Greek population in Turkey was forced to leave their ancestral homelands of Ionia, Pontus and Eastern Thrace. Those families didn't see themselves as Turkish -- they were Greek, even if they weren't from Greece per se.

That was part of the problem. The new Turkish state saw them as a threat -- much like the Armenians -- and during the 1919-1922 Greco-Turkish War, the Greeks in Turkey suffered numerous atrocities.

I don't know what James' father saw, but he escaped a country at war only a few years ahead of a massive population exchange involving 1.5 million people.

The desire to fit in to his new country -- to not have a target on his back because of his identity -- must have appealed to him greatly. He changed Hatjimathios to Matthews, settled in New Jersey, married an American woman from North Carolina named Inez Juanita Langley, and began a new life.

Lambros James Matthews was my grandfather's cousin. And it was 100 years ago that *his* father, Mathios Hatjimathios, came to America.

Wednesday, September 15, 2021

Another exercise

This past month, I spent some time last month at another exercise. Like the one I did in December 2020, it was pointless. Unlike that one, this one was also a complete mess, for the following reasons:

I got the phone call about the guy who got COVID on Friday afternoon. I got tested immediately, but still had to get quarantive throughout the whole weekend. Not fun at all.

- Poor design. We were tacked on to an already existing exercise that was happenening somewhere else. It was as if somebody, somewhere, said, "Hey, wouldn't it be great if we also played along?" And because that somebody was a senior ranking person, thatis what happened.

- There were ad hoc last minute pesonnel fills that went against the whole "Train as you fight" methodology. The training unit doesn't have enough people to do the stuff it wanted to do, so it tapped my workplace for backfill. Rather than go back to Senior Somebody and say, "we don't have the people to even do the exercise, let alone what it would take in a real world scenario," they slapped together a team so they could "make it happen."

- Organizers couldn't figure out if we were going to do 24-hour operations or not. This is kind of a big deal for civilians, because we have timesheets to fill out and we get paid overtime. However, as the only civilian involved, nobody cared about that. I suspect that there was a conversation that went like this: A."We need two captains." B."Best I can do is one captain, one civilian." A:"Ok that's fine." B:"By the way, you should kn-" A:"If I have two bodies, that's all I'm worried about."

- We didn't have good security. The room we occupied wasn't built to handle classified information, but someone in charge told us, "I'll assume risk." Well OK then. Your career's on the line.", I thought.

- COVID infections. The guy sitting next to me got COVID, and I had to go get my brain stabbed. Not fun.

- Flight data was not coordinated with the higher headquarters, which was focused on that other location. So as we tried to move people in and out of the exercise country, we kept running into problems with flight information. The ad hoc solution was to use a proxy, but proxy information leads you to GIGO (garbage in, garbage out) problems. There's simply no getting around bad data.

- Poor simulation data. In exercises, there's a certain amount of stuff that's made up to prevent NIMBY freak-outs from the host nation. This is understandable. However, the made-up places have to be credible. How many busses would it take to move X number of people from Here to There? And how long would it take? I don't know -- does your made-up pace have highway access? Does it have bridges with an appropriate weight allowance? If you want a credible test of the staff, you need a credible scenario.

I got the phone call about the guy who got COVID on Friday afternoon. I got tested immediately, but still had to get quarantive throughout the whole weekend. Not fun at all.

Wednesday, September 08, 2021

Five sisters for four brothers

Henry Krecklau wanted to get married, but ... he didn't want to work too hard at it.

The Krecklau family in 1900. Back row, from left to right: Ed, Emil, Bertha, Adolph. Front row: William, Johann, Justina, Henry

The Krecklau family in 1900. Back row, from left to right: Ed, Emil, Bertha, Adolph. Front row: William, Johann, Justina, Henry

Fortunately, he was the youngest of six children, and therefore could solicit recommendations from his siblings and sisters-in-law.

Henry's only sister Bertha got married 1900, the year she turnd 19. Adolph, the fourth oldest, saw no reason to wait, and married Lydia Arlt in December 1903 when he was 19.

Feeling the pressure, Emil -- the oldest -- then married Bertha Martha Schauer in 1905, just after turning 28.

Edward, the second oldest, took the easy route and married Bertha's sister Wilhelmine ("Minnie") Schauer in 1907 when he was 29. He unwittingly set a precedent.

So as Henry neared his 21st birthday in 1909, I imagine him asking Bertha and Minnie for input. If he did, they might have replied, "Well, our sister 'Tillie' turns 20 this year."

Now, I have no details of their courtship, nor any idea how well matched they were, but they at least found each other good enough. Henry Krecklau and Ottilie Schauer got married that year.

(Henry's older brother Willam, the last of the six, married Emma Stradtman in 1910, when he was 24.)

By 1912, Henry and Tillie had two sons together, and all seemed well until tragedy struck in 1914. That year, Tillie experienced complications following an operation for appendicitis. She developed an abcess, and passed away within three weeks of her surgery. That left Henry alone with his two sons, aged four and two.

In those days, it was more common for the recently widowed with children at home to remarry quickly, and again, Henry turned to family for recommendations.

But it wouldn't be the Schauer sisters; instead, William's wife Emma Stradtman referred Henry to *her* younger sister named Wilhelmina (another "Minnie").

Emma's recommendation appears to have been a good one, because Henry and Minnie married a year later. They would go on to add three daughters to Henry's two sons, and live a long life together.

So, what does this story have to do with my family? Well, that rather severe-looking mother in that top picture from 1900 is Justine Krecklau, née Kottke. She was my step-3x great-grandfather Christoph Kottke's older sister.

The Krecklau family in 1900. Back row, from left to right: Ed, Emil, Bertha, Adolph. Front row: William, Johann, Justina, Henry

The Krecklau family in 1900. Back row, from left to right: Ed, Emil, Bertha, Adolph. Front row: William, Johann, Justina, HenryFortunately, he was the youngest of six children, and therefore could solicit recommendations from his siblings and sisters-in-law.

Henry's only sister Bertha got married 1900, the year she turnd 19. Adolph, the fourth oldest, saw no reason to wait, and married Lydia Arlt in December 1903 when he was 19.

Feeling the pressure, Emil -- the oldest -- then married Bertha Martha Schauer in 1905, just after turning 28.

Edward, the second oldest, took the easy route and married Bertha's sister Wilhelmine ("Minnie") Schauer in 1907 when he was 29. He unwittingly set a precedent.

So as Henry neared his 21st birthday in 1909, I imagine him asking Bertha and Minnie for input. If he did, they might have replied, "Well, our sister 'Tillie' turns 20 this year."

Now, I have no details of their courtship, nor any idea how well matched they were, but they at least found each other good enough. Henry Krecklau and Ottilie Schauer got married that year.

(Henry's older brother Willam, the last of the six, married Emma Stradtman in 1910, when he was 24.)

By 1912, Henry and Tillie had two sons together, and all seemed well until tragedy struck in 1914. That year, Tillie experienced complications following an operation for appendicitis. She developed an abcess, and passed away within three weeks of her surgery. That left Henry alone with his two sons, aged four and two.

In those days, it was more common for the recently widowed with children at home to remarry quickly, and again, Henry turned to family for recommendations.

But it wouldn't be the Schauer sisters; instead, William's wife Emma Stradtman referred Henry to *her* younger sister named Wilhelmina (another "Minnie").

Emma's recommendation appears to have been a good one, because Henry and Minnie married a year later. They would go on to add three daughters to Henry's two sons, and live a long life together.

So, what does this story have to do with my family? Well, that rather severe-looking mother in that top picture from 1900 is Justine Krecklau, née Kottke. She was my step-3x great-grandfather Christoph Kottke's older sister.

Tuesday, September 07, 2021

Remembering Frances Perkins on Labor Day

On Memorial Day, we remember service members killed in war. On Veteran's Day, we think of those who've served in the military. On religious holidays, we remember why we have them.

For Labor Day, it seems appropriate to remember what labor has accomplished to make workplaces better.

Frances Perkins wasn't the first Secretary of Labor, but as Franklin Roosevelt's appointment for the position (and the first female Cabinet Secretary overall), she's probably the most memorable one.

When Roosevelt asked her to serve as Secretary of Labor in 1933, "She told him only if he agreed with her goals: 40-hour work week, minimum wage, unemployment and worker’s compensation, abolition of child labor, federal aid to the states for unemployment, Social

Security, a revitalized federal employment service, and universal health insurance. He agreed."

Perhaps you've been the beneficiary of one of those things. Perhaps not. But if you are, you now know who to thank.

For Labor Day, it seems appropriate to remember what labor has accomplished to make workplaces better.

Frances Perkins wasn't the first Secretary of Labor, but as Franklin Roosevelt's appointment for the position (and the first female Cabinet Secretary overall), she's probably the most memorable one.

When Roosevelt asked her to serve as Secretary of Labor in 1933, "She told him only if he agreed with her goals: 40-hour work week, minimum wage, unemployment and worker’s compensation, abolition of child labor, federal aid to the states for unemployment, Social

Security, a revitalized federal employment service, and universal health insurance. He agreed."

Perhaps you've been the beneficiary of one of those things. Perhaps not. But if you are, you now know who to thank.

Monday, September 06, 2021

Peter Boyer

Although the British evacuated Boston in March 1776, George Washington knew that they would be back, and calculated that they would attack New York City.

It made sense. New York was America's busiest port, and by controlling the Hudson River, the British could cut off New England from the mid-Atlantic colonies. To defend the city, Washington moved his army of 20,000 Continental soldiers to Manhattan (which at that time contained the full extent of the city).

The British used Staten Island as a staging base. Begining in late-June, 130 ships shuttled in soldiers from Nova Scotia in preparation for the assault. By mid-August, 32,000 redcoats (including 8000 Hessian merceneries) were in position for the upcoming battle for New York. [Source]

The American colonies had already declared independence at this point, and on July 9th tore down the statue of George III that stood at Manhattan's southern tip. On that same day, Pennsylvania's Northampton County "approved an added enlistment bounty of £3 per recruit," and militia Captain John Arndt began enlisting soldiers.

Among the enlistees was a second-generation German immigrant named Peter Boyer. His father Leonard had immigrated to Pennsylvania with his wife and daughter Anna Maria in 1741; Peter was born seven years later. As Peter and Anna Maria grew up, they married into other German families around the Clearfield, Northampton County area.

Anna Maria married another "Pennsylvania Deutsch" named Johann Jacob Engler; they had eight children together. Peter and his wife Anna Christina had two boys: Leonhart, 8, and Abraham, 3.

Captain Arndt's company -- along with three others -- formed a battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Peter Kichline in what was called the "Flying Camp." Unfortunately, only one of the companies was at full strength (108 soldiers). Ardt's was close with 87, but the other two did not even reach half of the required number. As a result, Kichline's battalion consisted of a mere 268 privates, with 55 officers, NCOs, and support staff.

Regardless of its readiness, Arndt's company departed shortly before August 5th, and arrived in Long Island on August 26th. Kichline's battalion was placed under Lord Stirling (William Alexander) as their brigade commander, and place on the right of the American line. It was just in time -- the British began their landings on Long Island that night.

Because Washington had poor intelligence regarding British plans, he split his forces between Manhattan and Long Island to try to guard both. The ten thousand soldiers on Long Island -- under General Israel Putnam -- fortified a position in the Brooklyn Heights. Putnam also posted troops at the four passes through which the British forces could approach (Gowanus [1), Flatbush [2), Bedford [3], Jamaica [4]). (Click the picture below for a better view.)

[Map Source]

[Map Source]

British General Howe sent a force of 5000 soldiers under Lt. Col. Grant to attack William Alexander's force along the Gowanus Road. He sent his Hessian troops to attack along the Flatbush road. But he marched his his main force though the Jamaica pass in a flanking maneuver.

When the commander guarding the Jamaica pass heard that the British were attacking the American right and center, he abandoned his position to help. It was an amateur move -- by the time he got back in position, Howe had already slipped past.

By 9:00 a.m. on August 27th, Howe's flanking maneuver had swept aside the Continentals guarding the Flatbush and Bedford passes. "General John Sullivan organized many of his men and made a defensive stand at Baker's Tavern. They were soon captured by von Heister's Hessians." [Source]

By 11:30 AM, William Alexander's troops were overwhelmed by Grant's superior numbers. Most of the Patriots (including Kichline's battalion) tried to escape and fled toward Gowanus Creek [5]. When Alexander learned that his line of retreat back to the Brooklyn Heights was blocked, he launched a series of counterattacks with about 250 Maryland troops, commanded by Major Mordecai Gist (the "Maryland 400"). Fewer than a dozen made it back to the Brooklyn Heights. [Source]

This video explains the Battle of Long Island better than any text I could write.

The Americans had lost the battle, but Washington was able to evacuate Putnam's force to Manhattan on August 30th. They would live to fight another day.

But given that Alexander's brigade had borne the brunt of the loss, what became of Arndt's company?

Peter's sons Leonhart and Abraham were thus left fatherless, and -- within three years -- motherless, too. Anna Christina died in 1779.

Peter's sons Leonhart and Abraham were thus left fatherless, and -- within three years -- motherless, too. Anna Christina died in 1779.

According to American Boyers, written by Rev. Charles C. Boyer in 1915, Leonhart was apprenticed out to a cobbler. "On March 9, 1779, [Leonghart's] guardian Caspar Doll, indentured him for nine years to Valentine Tvletz, shoemaker, of Plainfield Twp., Northampton Co., Pa." [Source]

From what I can tell, Abraham grew up and moved to nearby Berks County, where he raised a large family. One of his sons, George W. Boyer, served in the Civil War.

George's daughter Mary had a daugher named Nancy, who had another daughter Mary, who married a coal miner in western Pennsylvania named Edward Jones. That was my great-grandfather.

Which makes Peter Boyer my 6x great-grandfather.

It made sense. New York was America's busiest port, and by controlling the Hudson River, the British could cut off New England from the mid-Atlantic colonies. To defend the city, Washington moved his army of 20,000 Continental soldiers to Manhattan (which at that time contained the full extent of the city).

The British used Staten Island as a staging base. Begining in late-June, 130 ships shuttled in soldiers from Nova Scotia in preparation for the assault. By mid-August, 32,000 redcoats (including 8000 Hessian merceneries) were in position for the upcoming battle for New York. [Source]

The American colonies had already declared independence at this point, and on July 9th tore down the statue of George III that stood at Manhattan's southern tip. On that same day, Pennsylvania's Northampton County "approved an added enlistment bounty of £3 per recruit," and militia Captain John Arndt began enlisting soldiers.

Among the enlistees was a second-generation German immigrant named Peter Boyer. His father Leonard had immigrated to Pennsylvania with his wife and daughter Anna Maria in 1741; Peter was born seven years later. As Peter and Anna Maria grew up, they married into other German families around the Clearfield, Northampton County area.

Anna Maria married another "Pennsylvania Deutsch" named Johann Jacob Engler; they had eight children together. Peter and his wife Anna Christina had two boys: Leonhart, 8, and Abraham, 3.

Captain Arndt's company -- along with three others -- formed a battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Peter Kichline in what was called the "Flying Camp." Unfortunately, only one of the companies was at full strength (108 soldiers). Ardt's was close with 87, but the other two did not even reach half of the required number. As a result, Kichline's battalion consisted of a mere 268 privates, with 55 officers, NCOs, and support staff.

Regardless of its readiness, Arndt's company departed shortly before August 5th, and arrived in Long Island on August 26th. Kichline's battalion was placed under Lord Stirling (William Alexander) as their brigade commander, and place on the right of the American line. It was just in time -- the British began their landings on Long Island that night.

Because Washington had poor intelligence regarding British plans, he split his forces between Manhattan and Long Island to try to guard both. The ten thousand soldiers on Long Island -- under General Israel Putnam -- fortified a position in the Brooklyn Heights. Putnam also posted troops at the four passes through which the British forces could approach (Gowanus [1), Flatbush [2), Bedford [3], Jamaica [4]). (Click the picture below for a better view.)

[Map Source]

[Map Source]British General Howe sent a force of 5000 soldiers under Lt. Col. Grant to attack William Alexander's force along the Gowanus Road. He sent his Hessian troops to attack along the Flatbush road. But he marched his his main force though the Jamaica pass in a flanking maneuver.

When the commander guarding the Jamaica pass heard that the British were attacking the American right and center, he abandoned his position to help. It was an amateur move -- by the time he got back in position, Howe had already slipped past.

By 9:00 a.m. on August 27th, Howe's flanking maneuver had swept aside the Continentals guarding the Flatbush and Bedford passes. "General John Sullivan organized many of his men and made a defensive stand at Baker's Tavern. They were soon captured by von Heister's Hessians." [Source]

By 11:30 AM, William Alexander's troops were overwhelmed by Grant's superior numbers. Most of the Patriots (including Kichline's battalion) tried to escape and fled toward Gowanus Creek [5]. When Alexander learned that his line of retreat back to the Brooklyn Heights was blocked, he launched a series of counterattacks with about 250 Maryland troops, commanded by Major Mordecai Gist (the "Maryland 400"). Fewer than a dozen made it back to the Brooklyn Heights. [Source]

This video explains the Battle of Long Island better than any text I could write.

The Americans had lost the battle, but Washington was able to evacuate Putnam's force to Manhattan on August 30th. They would live to fight another day.

But given that Alexander's brigade had borne the brunt of the loss, what became of Arndt's company?

According to the one casualty list we have out of the four companies (the other three are missing or were just never taken), in Captain Arndt’s company 21 men were killed or captured at Long Island. Captain Arndt’s company largely managed to escape, but Captains Jayne and Hagenbuch were captured, along with Colonel Kichline. [Source]Sadly, on the list of "Names and Ranks of those killed to taken on Long Island the 27th Day of August 1776," Peter Boyer was #10.

Peter's sons Leonhart and Abraham were thus left fatherless, and -- within three years -- motherless, too. Anna Christina died in 1779.

Peter's sons Leonhart and Abraham were thus left fatherless, and -- within three years -- motherless, too. Anna Christina died in 1779. According to American Boyers, written by Rev. Charles C. Boyer in 1915, Leonhart was apprenticed out to a cobbler. "On March 9, 1779, [Leonghart's] guardian Caspar Doll, indentured him for nine years to Valentine Tvletz, shoemaker, of Plainfield Twp., Northampton Co., Pa." [Source]

Upon adulthood, he became to Snowden Twp., Allegheny Co., Pa., at Croca's Tan yard. In 1812 we find him building a log house on the Library road. He married Mary Deemer, of Westmoreland Co., Pa., and her parents, like his, were from Eastern Pennsylvania. She was born 1771, and died Dec. 25, 1859. They are both buried at the Peter's Creek Baptist Church, Library, Pa. Their children were: Jacob, Elizabeth, Mary, Peter, Andrew, Anne, John.That author said Leonhart was "probably" Peter's only son, but -- for whatever reason -- did not know of Abraham's existence.

From what I can tell, Abraham grew up and moved to nearby Berks County, where he raised a large family. One of his sons, George W. Boyer, served in the Civil War.

George's daughter Mary had a daugher named Nancy, who had another daughter Mary, who married a coal miner in western Pennsylvania named Edward Jones. That was my great-grandfather.

Which makes Peter Boyer my 6x great-grandfather.

Sunday, September 05, 2021

Stairway to ...?

Saturday, September 04, 2021

Benjamin Franklin

Please see the comment before continuing.

******

Benjamin Franklin was a terrible father.

Benjamin Franklin was a terrible father.

His son William was born just before his marriage to Deborah Read in 1730. Perhaps because of the circumstances of his birth -- despite being taken in by the family -- William seems to have grown up with a chip on his shoulder.

The apple didn't seem to fall far from the tree, though, because William also had an illegitimiate child -- William Temple Franklin. For whatever reason, Benjamin felt quite fond of Temple, which probably just irritated William further.

The animosity became political. While Benjamin Franklin was a great advocate for the American cause, William was a Loyalist. In fact, he became what would be the last Royal Governor of New Jersey. As the Revolutionary War wound down, William moved to England with Temple, and the two never saw Benjamin Franklin again. [Source]

Benjamin was a terrible husband, too.

In November 1764, he left for England, where he would stay until 1775. Even after Deborah suffered a stroke (1768) and stopped writing to him (1773), he still refused to return. She died in Deember 1774, without having seen him for the last ten years of her life. [Source]

Benjamin and Deborah had a son (Francis) and a daughter (Sarah) together, but Francis died from smallpox when he was four years-old. Sarah grew up and had a family of her own, but took her husband's name -- Bache. As a result, the only descendents of Benjamin Franklin with his family name are in England.

Benjamin did, however, have many brothers and sisters. In fact, his immediate-older sister was also named Deborah; he was born in 1706, she was born in 1705.

Deborah Franklin married a fellow named Joseph Scull on February 1, 1729, and the two would go on to have 15 children. I'm not sure if all of them survived to adulthood, but the 11th seems to have been named after his uncle: Benjamin Franklin Scull.

That was interesting to me, because Scull was my grandmother Eleanor's middle name. And it was her middle name because it was *her* mother's maiden name.

Benjamin Franklin Scull was my great-grandmother Anna Mae Scull's great-great-grandfather, making Ben Franklin my 6th great-granduncle.

******

Benjamin Franklin was a terrible father.

Benjamin Franklin was a terrible father.His son William was born just before his marriage to Deborah Read in 1730. Perhaps because of the circumstances of his birth -- despite being taken in by the family -- William seems to have grown up with a chip on his shoulder.

The apple didn't seem to fall far from the tree, though, because William also had an illegitimiate child -- William Temple Franklin. For whatever reason, Benjamin felt quite fond of Temple, which probably just irritated William further.

The animosity became political. While Benjamin Franklin was a great advocate for the American cause, William was a Loyalist. In fact, he became what would be the last Royal Governor of New Jersey. As the Revolutionary War wound down, William moved to England with Temple, and the two never saw Benjamin Franklin again. [Source]

Benjamin was a terrible husband, too.

In November 1764, he left for England, where he would stay until 1775. Even after Deborah suffered a stroke (1768) and stopped writing to him (1773), he still refused to return. She died in Deember 1774, without having seen him for the last ten years of her life. [Source]

Benjamin and Deborah had a son (Francis) and a daughter (Sarah) together, but Francis died from smallpox when he was four years-old. Sarah grew up and had a family of her own, but took her husband's name -- Bache. As a result, the only descendents of Benjamin Franklin with his family name are in England.

Benjamin did, however, have many brothers and sisters. In fact, his immediate-older sister was also named Deborah; he was born in 1706, she was born in 1705.

Deborah Franklin married a fellow named Joseph Scull on February 1, 1729, and the two would go on to have 15 children. I'm not sure if all of them survived to adulthood, but the 11th seems to have been named after his uncle: Benjamin Franklin Scull.

That was interesting to me, because Scull was my grandmother Eleanor's middle name. And it was her middle name because it was *her* mother's maiden name.

Benjamin Franklin Scull was my great-grandmother Anna Mae Scull's great-great-grandfather, making Ben Franklin my 6th great-granduncle.

"Parking space included."

Friday, September 03, 2021

Anna (Hannah?) Annie Edmonds

There was a show in the 1970s called the Brady Bunch.

One of the things I'd never wondered was "What if Greg Brady married Marsha?" That is ... until now.

"A lovely lady"

Anna Edmonds came from Bristol, in southwestern England. William was from Wales, which is just north across the Bristol Channel. Both were big coal mining areas, so it's likely that William had gone to Bristol to work.

The two married in 1882, and moved to the United States after their daughter was born. There, they had two sons -- William and Edward -- along with five other children.

Sadly, William (the elder) was gone by the time of the 1900 census, leaving Anna to take care of eight children – with the youngest only a year and a half old.

"A man named … Flook"

Joseph Flook and his wife Roseanna Rogers were also from Wales. They married in 1878 in Llanfihangel, which today is a mere hour's drive from Bristol. Their daughter was born in 1880 in Talywain, and they moved to the U.S. in 1883.

After their arrival, they had more two daughters -- Gertrude and Thursa -- and then three boys.

Sadly, Roseanna passed away in 1898 from complications following the birth of their youngest, and Joseph was left with six children – the youngest a mere two months old.

“When the lady met this fellow…”

Joseph and Anna probably already knew each other. They’d lived in the same coal mining community for several years and were actually on the *same census page.* Their houses were probably right down the street from each other.

Sometime between the census in June 1900 and June 1901, Joseph and Anna joined their two families together. With 7 children from Anna’s first marriage and 5 from Joseph’s (the oldest of each having moved out) it would certainly have been crowded.

Sometime between the census in June 1900 and June 1901, Joseph and Anna joined their two families together. With 7 children from Anna’s first marriage and 5 from Joseph’s (the oldest of each having moved out) it would certainly have been crowded.

And then in true “yours, mine, and ours” fashion, they added three more.

But wait, there’s more

At this point, you might think that 17 children – grown or not – makes a crazy enough story. But in 1901, Anna’s son William turned 16. Joseph’s daughter Thursa was six months younger.

Now, there are many details in this situation that have not made it into traceable records, but one thing is clear – Anna’s son William married Joseph’s daughter Thursa in 1903. That made William simultaneously Joseph’s step-son and son-in-law. (This just about broke the family tree.)

And through my great-grandfather Edward, Thursa became my great-great-grandmother Anna’s both step-daughter and daughter-in law.

And through my great-grandfather Edward, Thursa became my great-great-grandmother Anna’s both step-daughter and daughter-in law.

Mr. Flook’s expression in this picture summed up my reaction nicely.

One of the things I'd never wondered was "What if Greg Brady married Marsha?" That is ... until now.

"A lovely lady"

Anna Edmonds came from Bristol, in southwestern England. William was from Wales, which is just north across the Bristol Channel. Both were big coal mining areas, so it's likely that William had gone to Bristol to work.

The two married in 1882, and moved to the United States after their daughter was born. There, they had two sons -- William and Edward -- along with five other children.

Sadly, William (the elder) was gone by the time of the 1900 census, leaving Anna to take care of eight children – with the youngest only a year and a half old.

"A man named … Flook"

Joseph Flook and his wife Roseanna Rogers were also from Wales. They married in 1878 in Llanfihangel, which today is a mere hour's drive from Bristol. Their daughter was born in 1880 in Talywain, and they moved to the U.S. in 1883.

After their arrival, they had more two daughters -- Gertrude and Thursa -- and then three boys.

Sadly, Roseanna passed away in 1898 from complications following the birth of their youngest, and Joseph was left with six children – the youngest a mere two months old.

“When the lady met this fellow…”

Joseph and Anna probably already knew each other. They’d lived in the same coal mining community for several years and were actually on the *same census page.* Their houses were probably right down the street from each other.

Sometime between the census in June 1900 and June 1901, Joseph and Anna joined their two families together. With 7 children from Anna’s first marriage and 5 from Joseph’s (the oldest of each having moved out) it would certainly have been crowded.

Sometime between the census in June 1900 and June 1901, Joseph and Anna joined their two families together. With 7 children from Anna’s first marriage and 5 from Joseph’s (the oldest of each having moved out) it would certainly have been crowded.And then in true “yours, mine, and ours” fashion, they added three more.

But wait, there’s more

At this point, you might think that 17 children – grown or not – makes a crazy enough story. But in 1901, Anna’s son William turned 16. Joseph’s daughter Thursa was six months younger.

Now, there are many details in this situation that have not made it into traceable records, but one thing is clear – Anna’s son William married Joseph’s daughter Thursa in 1903. That made William simultaneously Joseph’s step-son and son-in-law. (This just about broke the family tree.)

And through my great-grandfather Edward, Thursa became my great-great-grandmother Anna’s both step-daughter and daughter-in law.

And through my great-grandfather Edward, Thursa became my great-great-grandmother Anna’s both step-daughter and daughter-in law.Mr. Flook’s expression in this picture summed up my reaction nicely.

Yokota TDY

From 15-19 August, and then 22 Aug to 2 Sep, I went TDY to Yokota Air Base for an exercise. Staying in a Japanese hotel was pretty interesting.

The room was small, with the bed placed right next to the desk, and no formal closet.

The room was small, with the bed placed right next to the desk, and no formal closet.

The bed was right next to the window, which offered a great of the area outside Fussa Station (福生駅).

The bed was right next to the window, which offered a great of the area outside Fussa Station (福生駅).

Breakfast was complimentary, and the vending machine in the lobby sold beer.

Breakfast was complimentary, and the vending machine in the lobby sold beer.

The room was small, with the bed placed right next to the desk, and no formal closet.

The room was small, with the bed placed right next to the desk, and no formal closet.

The bed was right next to the window, which offered a great of the area outside Fussa Station (福生駅).

The bed was right next to the window, which offered a great of the area outside Fussa Station (福生駅).

Breakfast was complimentary, and the vending machine in the lobby sold beer.

Breakfast was complimentary, and the vending machine in the lobby sold beer.

Thursday, September 02, 2021

Anna Thieler

Anna spent her whole life thinking she was from Germany.

It made sense. She knew that she was born in Europe, that her family moved to the U.S. soon after she was born (1885), and that her parents spoke German at home.

Besides, there wasn't really anyone to correct her. Her mother died in childbirth when she was six, and her father didn't speak much about the days before he married his second wife.

In the 1900 census, Father listed Germany as his place of birth, as well as Anna's step-mother's.

By 1910, Anna married, and lived with her five year-old son and her native-born husband from Illinois. Trivialities like where her parents came from 25 years before didn't really matter anymore. She was American now, much like her siblings who'd started Anglicizing their last name: "Tyler."

In 1917, her father passed away, putting more distance from her past. Through 1920 and 1930 censuses, Anna repeated her mistake.

Although the 1940 census didn't ask about parents' countries of origin, Anna didn't have the chance to answer.

Anna's son married in1930 and her daughter-in-law moved in. A year later, Anna passed away at the age of 46, never understanding where she was really came from, much less why her parents wanted to leave.

Anna was not from Germany. Nor was she from Austria, as her brother John Paul and older sister Gisela thought. Gisela was on the right track, though – she'd at least guessed that *Magyar* was her parent's "native tongue."

And therein lies a clue as to why the Thieler family left Szentjanos ("Sant John"), Hungary in 1887. The newly autonomous Kingdom of Hungary – still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – had recently begun a policy of "Magyarization." They wanted Hungary for Hungarians. And as ethnic Germans on the western side of the country, the Thieler family apparently felt that better opportunities lay elsewhere.

It is a strange thing that we can learn such details about a person who lived a hundred years ago, and yet to have never once thought to ask those who would have known them best.

It is a strange thing that we can learn such details about a person who lived a hundred years ago, and yet to have never once thought to ask those who would have known them best.

As a ten year-old, I certainly would have never thought to ask Anna's son, whom I'd met, about his mother. I just didn't know what I didn't know.

Anna's son is pictured here – he's the gentleman on the left. And in the center there – that's my brother.

This picture was taken in 1985. Grandpa Roy passed away in 1988.

I looked up the address that the family lived at when they first arrived. This house was built in 1888, which means that Anna Thieler was among its first occupants.

I looked up the address that the family lived at when they first arrived. This house was built in 1888, which means that Anna Thieler was among its first occupants.

It made sense. She knew that she was born in Europe, that her family moved to the U.S. soon after she was born (1885), and that her parents spoke German at home.

Besides, there wasn't really anyone to correct her. Her mother died in childbirth when she was six, and her father didn't speak much about the days before he married his second wife.

In the 1900 census, Father listed Germany as his place of birth, as well as Anna's step-mother's.

By 1910, Anna married, and lived with her five year-old son and her native-born husband from Illinois. Trivialities like where her parents came from 25 years before didn't really matter anymore. She was American now, much like her siblings who'd started Anglicizing their last name: "Tyler."

In 1917, her father passed away, putting more distance from her past. Through 1920 and 1930 censuses, Anna repeated her mistake.

Although the 1940 census didn't ask about parents' countries of origin, Anna didn't have the chance to answer.

Anna's son married in1930 and her daughter-in-law moved in. A year later, Anna passed away at the age of 46, never understanding where she was really came from, much less why her parents wanted to leave.

Anna was not from Germany. Nor was she from Austria, as her brother John Paul and older sister Gisela thought. Gisela was on the right track, though – she'd at least guessed that *Magyar* was her parent's "native tongue."

And therein lies a clue as to why the Thieler family left Szentjanos ("Sant John"), Hungary in 1887. The newly autonomous Kingdom of Hungary – still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – had recently begun a policy of "Magyarization." They wanted Hungary for Hungarians. And as ethnic Germans on the western side of the country, the Thieler family apparently felt that better opportunities lay elsewhere.

It is a strange thing that we can learn such details about a person who lived a hundred years ago, and yet to have never once thought to ask those who would have known them best.

It is a strange thing that we can learn such details about a person who lived a hundred years ago, and yet to have never once thought to ask those who would have known them best.As a ten year-old, I certainly would have never thought to ask Anna's son, whom I'd met, about his mother. I just didn't know what I didn't know.

Anna's son is pictured here – he's the gentleman on the left. And in the center there – that's my brother.

This picture was taken in 1985. Grandpa Roy passed away in 1988.

I looked up the address that the family lived at when they first arrived. This house was built in 1888, which means that Anna Thieler was among its first occupants.

I looked up the address that the family lived at when they first arrived. This house was built in 1888, which means that Anna Thieler was among its first occupants.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)