How many children has the person had, and how many of those children are living? [Source]

It was a deeply personal matter, but it was one that no echelon of government could comprehensively answer otherwise. Many states just didn’t collect information on infant mortality. To get some measure of visibility on the matter, the federal government addressed it in the census, and then published a report in 1912. [Source]

It was a deeply personal matter, but it was one that no echelon of government could comprehensively answer otherwise. Many states just didn’t collect information on infant mortality. To get some measure of visibility on the matter, the federal government addressed it in the census, and then published a report in 1912. [Source]“Why bother asking the question,” one might have argued, “if there isn’t anything we can do about it anyway?” For all of history up to the 19th century, no nation had ever been able to alter the course of disease. That was God’s purview, not government’s. How a person died was seen as an aspect of divine judgment.

However, for the first time in history, there *was* something government could do. Germ theory was rapidly replacing miasma theory as the cause of illness, and contemporary progressives were demanding that government make public health a matter of policy.

As cities and towns installed sewer lines, rates of cholera, typhoid, and dysentery fell. Yet without comprehensive metrics, there was no way of knowing which areas were lagging behind. As late 20th century management consultant Peter Drucker put it, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”

Up until about 1900, one’s date and cause of death were essentially private matters. Whatever information wasn’t part of a church record, wasn’t in an obituary, and didn’t go on a person’s gravestone just plain wasn’t public knowledge. A child might live and die without later generations knowing that they had ever existed.

Such was the case with Sarah Ann Mansell’s granddaughter Estella Dukes. Because Sarah Ann’s son James Fullard Dukes and his wife were regular churchgoers, the St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Barnesboro recorded Estella’s birth on 2 January 1899, her baptism on 26 March, and her burial on 25 July.

The church recorded the dates, but did not record the cause of her death. Whatever knowledge there may have been disappeared with that generation.

In 1906, Pennsylvania decided to change that, and began collecting death records. The state might not be able to prevent an individual child’s death, but the collective voices of its infants who were silenced by disease would no longer fade to obscurity.

Rather, the state could compile and analyze causes of death and use that informatoin to identify areas for improvement. With visibility on causes of death, the state could at least assess where the areas of greatest concern were. Perhaps it could even save a future child’s life.

So while Estella Dukes’ cause of death in 1899 may never be known, we know why Henry Mansell’s grandson Charles Irvin Brown died a month shy of his first birthday in 1907. Like Frances Kinkead, he died of cholera – a result of drinking water polluted by fecal matter.

Coincidentally, 1907 was the year Barnesboro got its first water reservoir. As the Northern Cambria Borough Office notes, “An adequate water supply was not provided until 1907 after several very disastrous fires. A reservoir was constructed in the western section of town.” [Source]

Coincidentally, 1907 was the year Barnesboro got its first water reservoir. As the Northern Cambria Borough Office notes, “An adequate water supply was not provided until 1907 after several very disastrous fires. A reservoir was constructed in the western section of town.” [Source]The reservoir may have been a fire management tool, but it is not coincidental that I can find no other record after that point of a Barnesboro resident dying from cholera.

There were other causes, of course. The tragedy of infant mortality touched many families.

James Birchall’s older brother Thomas had a son named Roland who died of bronchial pneumonia in 1909 when he was 13 months old. Thomas had another son named Edward who died of empyema in 1919 at two-and-a-half years-old, though by that point Thomas was not around to grieve him.

Henry Mansell Sr. had a grandson William who died in 1918 of pertusis (whooping cough) when he was two years-old. William was my grandmother’s cousin; his mother was Elizabeth (Smith) Mansell.

Henry Mansell Sr. had a grandson William who died in 1918 of pertusis (whooping cough) when he was two years-old. William was my grandmother’s cousin; his mother was Elizabeth (Smith) Mansell. Sarah Ann and Henry Mansell’s son Leonard had a daughter named Elizabeth who died of bronchitis in 1918 when she was two weeks old. Leonard had another daughter named Esther who died of endocarditis meningitis in 1927 at nearly three years old.

Sarah Ann and Henry Mansell’s son Leonard had a daughter named Elizabeth who died of bronchitis in 1918 when she was two weeks old. Leonard had another daughter named Esther who died of endocarditis meningitis in 1927 at nearly three years old.

The ability to track causes of death cast a spotlight on other problems, such as poor child-rearing practices. James Birchall’s brother William had a sister-in-law who scalded to death their third son, Clare Edward Carrig. The boy was 15 months old.

Death certificates also recorded problems with occupational safety. As explained in one journal in 1982, “Until the 1800s, many illnesses and premature causes of death were widely believed to be the results of acts of God or chance….”[Source]

Death certificates also recorded problems with occupational safety. As explained in one journal in 1982, “Until the 1800s, many illnesses and premature causes of death were widely believed to be the results of acts of God or chance….”[Source]In the mid-20th century, the thinking on occupational safety would shift toward better design and prevention, but that would be too late for those who died in the early 1900s.

Another of Sarah Ann Mansell’s grandchildren, William Leonard (Faith’s son) died in 1924, four days after a rock fall fractured his pelvis and crushed his bowels. He was 18 years-old.

James Birchall’s brother Thomas –- the man who lost two sons to childhood illnesses but wasn’t around to see the second -– was run down by a mine cart and instantly killed in 1917. He was 34.

James Birchall’s brother Thomas –- the man who lost two sons to childhood illnesses but wasn’t around to see the second -– was run down by a mine cart and instantly killed in 1917. He was 34.  James Birchall’s nephew Arthur Willard Dukes (son of his first wife’s brother Arthur) died by electrocution after coming in contact with a high tension electric wire at the transformer in 1926. He was 19.

James Birchall’s nephew Arthur Willard Dukes (son of his first wife’s brother Arthur) died by electrocution after coming in contact with a high tension electric wire at the transformer in 1926. He was 19. Of course, the mines of Cambia County weren’t always in a rush. Sometimes, they could be patient.

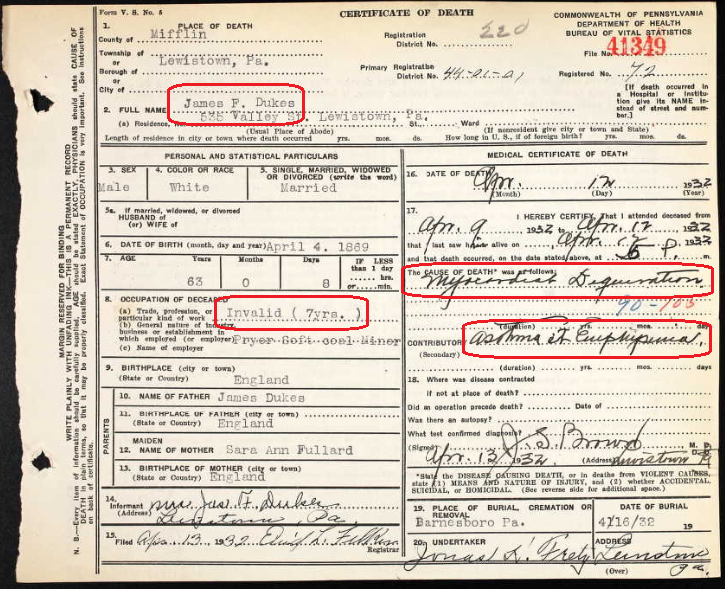

Of course, the mines of Cambia County weren’t always in a rush. Sometimes, they could be patient.Sarah Ann Mansell’s son James Fullard Dukes died slowly. Coal dust irritated his lungs to the point where he developed asthma and emphysema, and died at age 63 after having been an invalid for 7 years.

Like James Fullard Dukes, the Cambria County coal mines slowly killed Thomas Birchall’s nephew Thomas Edward Jones. He was born in 1917, and worked in the mines during the mid-20th century.

Like James Fullard Dukes, the Cambria County coal mines slowly killed Thomas Birchall’s nephew Thomas Edward Jones. He was born in 1917, and worked in the mines during the mid-20th century.“Black Lung,” as pneumoconiosis is more commonly known, was not well understood until the 1950s. By that point, the evidence was unmistakable that it was killing miners, and in 1969 the U.S. Congress created the Black Lung Disability Trust, of which Thomas Jones was a beneficiary until the day he died in 2003.

What began as a personal matter –- one's cause of death -– changed in the 20th century to become a matter of public interest. The expansion of the administrative state led to better conditions for both children and adults, workers and their dependents, parents and their descendants.

To me, the cause of death for Thomas Edward Jones – my grandfather – leaves me with mixed feelings. I am grateful for his sacrifices -- without them I would not be here -- but I am sad that they were ever necessary in the first place.

Perhaps 100 years from now, a future generation will look back say this same thing about the present time: "That was then; this is now. Let's continue to do better."

No comments:

Post a Comment